17 October 2024 • 6 minute read

Effect of patent term extensions on obviousness-type double patenting

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued its opinion in Allergan USA, Inc. v. MSN Laboratories Private Ltd., No. 24-1061 (Fed. Cir. 2024), holding that “a first-filed, first-issued, later-expiring claim cannot be invalidated by a later-filed, later-issued, earlier-expiring reference claim having a common priority date.” The decision, issued on August 13, 2024, clarifies the scope and applicability of Federal Circuit’s previous decision in In re Cellect, LLC, 81 F.4th 1216 (Fed. Cir. 2023). This opinion provides protections from obviousness-type double patenting (ODP) challenges for first-filed patents with a patent term adjustment based on its children that share the same priority date.

One of the generic defendants, Sun Pharmaceutical, has petitioned for rehearing en banc.

Overview of ANDA filings, the asserted patents, and patent term adjustments in the Viberzi® case

Generic drug manufacturers MSN Labs. and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. each filed Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to market and sell the generic version of Allergan’s Viberzi® drug product. The ANDA filings included Paragraph IV certifications with respect to the Orange Book-listed patents. Allergan subsequently sued the generic defendants in the District of Delaware under the Hatch-Waxman Act, asserting US Patent No. 7,741,356 (the 356 patent) – the parent patent – and its children: US Patent Nos. 8,344,011 (the 011 patent), and 8,609,709 (the 709 patent).

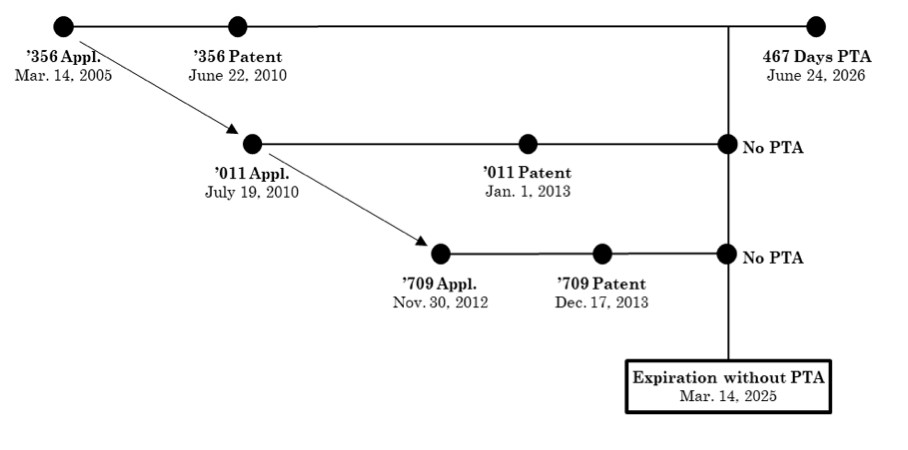

To account for delays in prosecution, the parent ’356 patent was awarded 1,107 days of patent term adjustment (PTA). However, when securing a patent term extension (PTE) due to FDA delays, Allergan disclaimed all but 467 days of the PTA. Accounting for this PTA (and not PTE, which was not relevant to the appeal), the ’356 patent will expire on June 24, 2026. The ’356 patent is set to expire after the two child patents at issue: the ’011 patent and the ’709 patent. Both child patents have the same priority date as the parent, were filed after the parent, and neither received any PTA, as there were no delays during prosecution.

The relationship between the filing, issuance, and expiration dates of these three patents was provided in the Federal Circuit’s opinion with the following figure:

During the litigation, the generic defendants argued that the ’356 patent’s claims were patentably indistinct, and thus invalid for ODP over certain claims of the ’011 patent and the ’709 patent.

Following a three-day bench trial, the district court agreed with the defendants, and found the ’356 patent invalid for ODP, citing In re Cellect. The district court found that “ODP for a patent that has received PTA, regardless [of] whether or not a terminal disclaimer is required or has been filed, must be based on the expiration date of the patent after PTA has been added.”

In other words, the district court ruled that for ODP determinations, the expiration dates of the patents in question, rather than the filing or issuance dates, should be compared.

Federal Circuit reverses district court: Clarifying when child patents are proper ODP references

On appeal, the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s decision, concluding that the claims of the ’011 and ’709 patents were not proper ODP references that could be used to invalidate the subject claim of the ’356 patent.

The Federal Circuit distinguished the facts and questions presented in Cellect from Allergan: “Cellect does not address, let alone resolve, any variation of the question presented here – namely, under what circumstances can a claim properly serve as an ODP reference – and therefore has little to say on the precise issue before us.” The court then stated that a “first-filed, first-issued, later-expiring claim cannot be invalidated by a later-filed, later-issued, earlier-expiring reference claim having a common priority date.”

The Federal Circuit reasoned that “[t]o hold otherwise – that a first-filed, first-issued parent patent having duly received PTA can be invalidated by a later-filed, later-issued child patent with less, if any, PTA – would not only run afoul of the fundamental purposes of ODP, but effectively abrogate the benefit Congress intended to bestow on patentees when codifying PTA.”

The Federal Circuit also clarified that the instant issue on appeal is distinguishable from Gilead Sciences., Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd., 753 F.3d 1208, 1215-17 (Fed. Cir. 2014), where the Federal Circuit held that a later-issued, but earlier expiring patent, may qualify as an ODP reference for invaliding an earlier-issued, but later-expiring patent. Instead, the ruling states that ’356 parent patent should be treated as the first-filed, first-issued patent in the family, It then sets the maximum period of exclusivity for the claimed subject matter and any patentably indistinct variants filed thereafter. Here, the ’356 patent was the first patent to be filed and first to be issued.

While the ’356 patent expires after the ’011 and ’709 patents, it would not be treated as a second expiring patent of the same invention. Instead, the ’356 patent sets the maximum exclusivity period for invention claimed therein.

Allergan’s impact on ODP doctrine: Key takeaways

Allergan brings clarity to the ODP doctrine by confirming that patent filing and issue dates, in addition to expiration dates, are relevant to analyzing ODP. Further, Allergan makes clear that the patent term of the parent patent sets the maximum period of exclusivity for the claimed subject matter and patentably indistinct variants that might be recited in any child patent, and not vice versa. The decision also affirms the value of PTA for a parent patent.

The Allergan decision reminds pharmaceutical companies and patentees that early planning with prosecution strategy (eg, what claims are pursued in the parent versus a child), regulatory (PTE) strategy, and enforcement decisions to ensure a complete understanding of exclusivities for drug products are key.

The case may still unfold further: while the Supreme Court denied the cert petition filed in In re Cellect, a petition for rehearing en banc in this case is still looming – as such, companies are advised continue to monitor these developments.

Find out more about the implications of this ruling by contacting either of the authors, or your DLA Piper relationship attorney.