27 February 2023 • 14 minute read

Understanding Monex: “Actual delivery” in metals commodities and the impact on digital assets and carbon commodities markets

The four-year legal battle between the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (the CFTC) and Monex Deposit Company, Monex Credit Company, and Newport Service Corporation, owner Michael Carabini, and founder Louis Carabini (together, Monex) over Monex’s Atlas trading platform has concluded.

In the consent order entered in December in Commodity Futures Trading Commission v. Monex Deposit Company, et al., US District Court for the Central District of California, Case No. 8:17-cv-01868-JVS-DFM (Monex) , Monex settled the charges pending against it for a total of $38 million in restitution and civil monetary penalties and injunctive measures. It also consented to several findings: specifically, that Monex had engaged in off-exchange transactions in violation of Section 4(a) of the Commodities Exchange Act (the CEA) and committed fraud in violation of Sections 4b(a)(2)(A) and (C) and 6(c)(1) of the CEA.

Two issues decided by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal during the litigation will survive the dispute and impact CFTC-regulated trading platforms: first, that the CFTC can sue “for fraudulently deceptive activity, regardless of whether it was also manipulative [for the market as a whole]”; and second, that the CEA’s “actual delivery” carveout requires “at least some meaningful degree of possession or control by the customer.”1

Factual and procedural background

The facts discussed in this alert were set out in the Monex Consent Order or the Ninth Circuit opinion. For ten years, until August 31, 2021, Monex allowed retail customers to trade gold, silver, platinum, and palladium on a leveraged basis. Such trades did not occur on a regulated exchange or board of trade. Instead, Monex operated a retail over-the-counter platform (Atlas) that allowed customers to speculate on precious metals price movements, with Monex acting as the transactional counterparty. Thousands of customers engaged in leveraged trading, many accounts were subject to a margin call or had trading positions force-liquidated, and most customer accounts realized losses, including from trading, interest charges, and other fees.

And Monex was not simply a passive platform operator. It actively solicited customers to engage in leveraged trading of precious metals by touting them as a hedge against inflation, political and economic uncertainty, civil unrest, and other factors, and claiming physical metals are intrinsically valuable, “unlike stocks and bonds” – on Monex’s website (including in a dedicated “Profit Opportunity” section), on live sales calls, and elsewhere. Monex’s sales representatives also told customers (and were incentivized to tell customers on account of Monex’s sales rep compensation structure) that leveraged trading was one way to achieve maximum profits, while Monex knew full well that a substantial amount of transactional information, which was not shared with customers, showed most leveraged Atlas accounts lost money.

CFTC’s investigation of Monex’s activities led to the complaint filed in federal court alleging violations of the CEA. Monex challenged that complaint on legal grounds, arguing it failed to state a cognizable claim. As discussed, Monex argued: (1) it could not be liable for fraud because the CFTC has not alleged Monex manipulated the market; and (2) it fell within the CEA’s actual delivery exception. The district court agreed and dismissed the CFTC complaint. However, the Ninth Circuit did not share the district court’s opinions on those issues and reversed and remanded the case back to the district court for further proceedings.

CEA fraud claims and the use or employment of manipulative or deceptive devices

Addressing the dismissal of the CFTC’s fraud claims against Monex, the Ninth Circuit started with the text of the operative statute, 7 U.S.C. § 9(1), which provides (with added emphasis):

It shall be unlawful for any person, directly or indirectly, to use or employ, or attempt to use or employ, in connection with any swap, or a contract of sale or any commodity in interstate commerce, or for future delivery on or subject to the rules of any registered entity, any manipulative or deceptive device or contrivance, in contravention of such rules and regulations as the Commission shall promulgate.

The crucial question was whether the emphasized text “allow[ed] stand-alone fraud claims or require[d] fraud-based manipulation” of the market.

The district court held fraud-based manipulation was required after concluding “that ‘or’ really meant ‘and.’” The Ninth Circuit felt “or” meant “or,” applied a disjunctive reading, and found the statutory text unambiguous. It held “[a]uthorizing claims against ‘[m]anipulative or deceptive’ conduct means what it says: the CFTC may sue for fraudulently deceptive activity, regardless of whether it was also manipulative [with respect to the market].” The Ninth Circuit therefore concluded the district court missed on the fraud issue as well and reversed and remanded for further proceedings.

The Ninth Circuit’s read of 7 U.S.C. § 9(1) makes it easier for prospective plaintiffs in the circuit to state a fraud claim and survive early pleading challenges. Had the Ninth Circuit sided with Monex, plaintiffs would have needed to plausibly plead fraud-based manipulation of the market, not just a stand-alone fraud claim for deceptive activity irrespective of market manipulation – but it did not. Commodities trading platforms should already have written anti-fraud procedures in place, but having and ensuring compliance with such procedures is all the more important given the Ninth Circuit’s opinion on the fraud pleading requirements.

“Off-exchange” transactions and the “actual delivery” exception

Section 4(a) of the CEA, which Monex was accused of violating, provides that it is unlawful to enter into a futures contract unless the contract is traded on an organized exchange or another trading facility that complies with the CEA and any CFTC-established requirements, or on a derivatives transaction execution facility. However, the CEA’s registration provisions do not apply to retail dealers who actually deliver the commodities to customers within 28 days.2

Since the CEA does not define “actual delivery,” the Ninth Circuit turned to Black’s Law Dictionary, which defines it as the “act giving real and immediate possession to the buyer or the buyer’s agent,” and to an Eleventh Circuit opinion, CFTC v. Hunter Wise Commodities, LLC, which applied Black’s as well and found that defendant could not “actually deliver” because it “did not possess or control an inventory of metals from which it could deliver to retail customers.”3 The Ninth Circuit concluded “the plain language tells us that actual delivery requires at least some meaningful degree of possession or control by the customer.”

Monex customers, in contrast, signed agreements ceding control of the metals to Monex. As the Ninth Circuit explained, Monex “customers never possess[ed] or control[led] any physical commodity. Instead, Monex stores the metals in depositories with which Monex has contractual relationships. Monex retains exclusive authority to direct the depository on how to handle the metals; investors and the depositories have no contractual relationships with each other. Customers can get their hands on the metals only by making full payment” – a difficult task for customers with very leveraged positions – “requesting specific delivery of metals, and having the metals shipped to themselves, a pick-up location, or an agent.”

The Ninth Circuit opined that it “is possible for this exception to be satisfied when the commodity sits in a third-party depository, but not when,” as in the case of Monex, the “metals are in the broker’s chosen depository, never exchange hands, and are subject to the broker’s exclusive control, and customers have no substantial, non-contingent interests.” The Ninth Circuit thus concluded that the district court had erred in finding (1) the “actual delivery” exception applied to Monex and (2) that it barred relief on the CFTC’s claims.

While Monex’s Atlas trading platform facilitated metals trading, the Monex case and Ninth Circuit opinions could impact other traditional commodities, developing voluntary carbon markets, and digital assets.

Traditional commodities

The effect of the Ninth Circuit’s interpretation of 7 U.S.C. § 2(c)(2)(D)(ii)(III)(aa)’s 28-days exception to the regulation of retail commodity transactions on traditional commodities is clear. Moving forward, litigants or those under CTFC investigation wishing to take advantage of that exception might now need to show “at least some meaningful degree of possession or control [of the commodity] by the customer.” However, Monex could have a crossover impact on future court and regulatory interpretations of the forward contract exclusion to the definition of a swap with respect to nonfinancial commodities under 7 U.S.C. § 1a(47)(B)(ii) as well.

For more than 30 years, the CFTC’s “Brent Interpretation” has calibrated the scope of the forward contract exclusion.4 The Brent Interpretation recognizes the purpose of a forward contract is to transfer commodity ownership not just price risk, and it focuses on whether sellers exhibit “intent to deliver,” while also allowing for the exclusion of “transactions which create enforceable obligations to deliver but in which delivery is deferred for reasons of commercial convenience or necessity.” Now, enterprising parties hoping for relief from the forward contract exclusion in the event of a long-deferred delivery might try to analogize to Monex, port over the “meaningful degree of possession or control” standard, and argue intent alone no longer suffices.

Carbon markets

Voluntary carbon markets facilitating the exchange of carbon credits verified by third-party standards are growing in number as more and more companies attach value to reducing their carbon footprint or, where they cannot reduce, purchasing rights to emit. But while voluntary, such markets are not beyond the reach of the CTFC. Indeed, the CFTC has found “environmental commodities” which can be “physically delivered and consumed” are nonfinancial commodities subject to regulation by the CFTC.5 The CFTC did not define “environmental commodity” but indicated intent to transfer ownership, not just price risk, and actual consumption, eg, compliance with a mandatory or voluntary program, can distinguish environmental commodity transactions, including carbon credits, from others that cannot be delivered.

Monex’s effect on ex post carbon transactions appears to fundamentally mirror a traditional commodities transaction. In an ex post transaction, the purchased offset (represented by the credit) has been achieved. So, as with a traditional commodity – eg, the metals in Monex – the offset exists and may potentially be transferred at the time of transacting. For example, a company seeking to offset omissions can buy a credit connected to a forestry project that has been grown and already sequestered carbon. In that case, “some meaningful degree of possession or control” of the credit and sequestered carbon is “actually deliverable” to buyers within the meanings of the 28-day and forward contract exclusions under Monex and the CEA.

Ex ante carbon transactions, however, potentially create a thought-provoking definitional question: what is the commodity – the credit or the carbon? In ex ante transactions, the sequestration has not occurred. So, keeping with the forestry example, the purchaser’s investment is helping grow the forest, and in return the purchaser gets a credit giving them the right to carbon the project expects to be captured in the future. If the credit is the commodity, then there is no meaningful difference from a regulatory/Monex standpoint between ex ante and ex post. In both cases the credit can be actually delivered at the time of transacting. But if the carbon is the commodity, Monex’s facts can be superimposed. That is, in an ex ante transaction, the buyer (Monex customer) buys the right to sequestered carbon (precious metals) on some future date represented by a carbon credit (purchase agreement), but the project developer/seller (Monex) continues to control the carbon until that date. In this scenario, there is no “actual delivery” within the meanings of the 28-day and forward contract exclusions, and the purchase would be subject to the CEA’s swap rules.

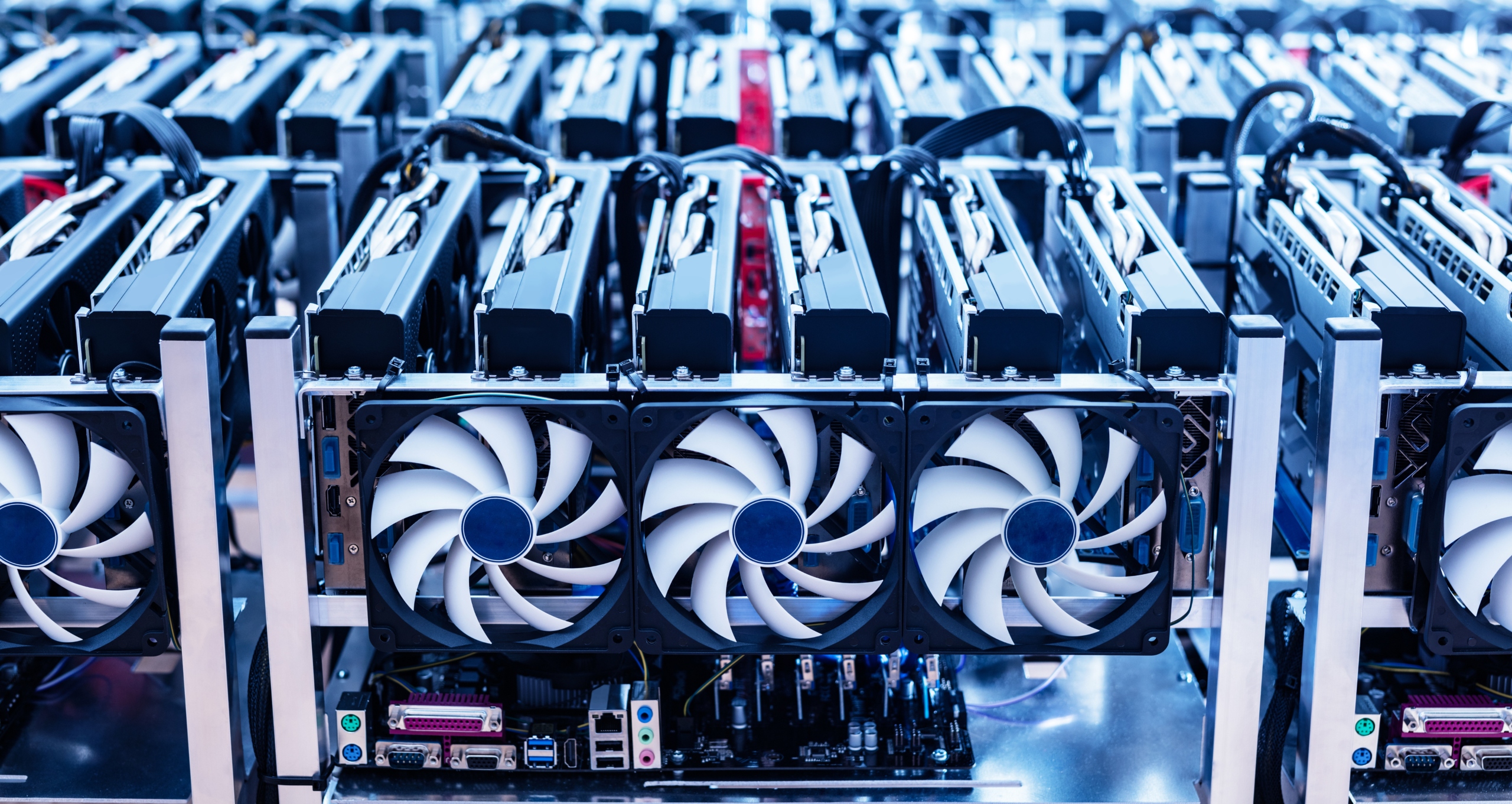

Digital assets

On June 24, 2020, the CFTC issued interpretive guidance regarding retail commodity transactions involving digital assets clarifying its view on the “actual delivery” exception for virtual currencies.6 The two main factors discussed as demonstrating “actual delivery” for virtual currencies7 were:

- A customer securing: (i) possession and control of the entire quantity of the commodity; and (ii) the ability to use it all freely in commerce no later than 28 days from the transaction date, and always thereafter and

- The offeror and counterparty seller retain no interest in, legal right, or control over any of the commodity after 28 days from the transaction date.

In other words, with respect to virtual currencies, the CFTC arguably may take a more restrictive view of “actual delivery” than the Ninth Circuit. The CFTC’s guidance indicates that, for virtual currencies, 28 days is a line of demarcation. Before the expiration of the 28-day period, the seller may retain some connection to the currency and not foreclose access to the exception. If after 28 days from the date of the transaction the seller has not fully relaxed their grip, the transaction will be subject to the CEA, including on-exchange trading and broker registration requirements.

In contrast, applying Monex’s “some meaningful degree of possession or control” standard to virtual currencies seemingly would allow a seller to continue to exercise some degree of domain after the 28-day period while still avoiding regulatory scrutiny and control by the CFTC. It remains to be seen whether the Ninth Circuit would extend the logic of Monex to virtual currency if presented such a case, but it appears to be a viable position unless and until the Court says otherwise.

Conclusion

The concept of delivery is critically important in defining the scope of the CFTC’s oversight and regulation of commodities transactions, including whether to apply the 28-day exception to retail transactions or to categorize agreements as forward or futures contracts. Monex took a swing at settling that concept in the context of traditional commodities, eg, precious metals, but as applied to carbon credit transactions and virtual currencies, Monex leaves open important questions or creates conflicts—the resolutions of which will impact the development and growth of those markets.

For any questions on the information provided in this Commodities Alert, please contact any of the authors of this alert or reach out to our team via DLAPiperCommodities@dlapiper.com.

[1] U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Comm'n v. Monex Credit Co., 931 F.3d 966, 972–77 (9th Cir. 2019).

[2] 7 U.S.C. § 2(c)(2)(D)(ii)(III)(aa).

[3] 749 F.3d 967, 980 (11th Cir. 2014).

[4] Statutory Interpretation Concerning Forward Transactions, 55 Fed. Reg., 39188, Sept. 25, 1990.

[5] Further Definition of “Swap,” “Security-Based Swap,” and “Security Based Swap Agreement”; Mixed Swaps; Security-Based Swap Agreement Recordkeeping, 77 Fed. Reg., 48233, Aug. 13, 2012.

[6] Retail Commodity Transactions Involving Certain Digital Assets, 85 Fed. Reg., 37734, June 24, 2020.

[7] With respect to defining what constitutes a “virtual currency” for regulatory purposes, the CFTC’s interpretative guidance in the Federal Register states:

The Commission continues to interpret the term ‘‘virtual currency’’ broadly. In the context of this interpretation, virtual currency: Is a digital asset that encompasses any digital representation of value or unit of account that is or can be used as a form of currency (i.e., transferred from one party to another as a medium of exchange); may be manifested through units, tokens, or coins, among other things; and may be distributed by way of digital ‘‘smart contracts,’’ among other structures. However, the Commission notes that it does not intend to create a bright line definition given the evolving nature of the commodity and, in some instances, its underlying public distributed ledger technology (‘‘DLT’’ or ‘‘blockchain’’).

It also provided that “the term ‘virtual currency’ for purposes of this interpretive guidance is meant to be viewed as synonymous with ‘digital currency’ and ‘cryptocurrency’ as well as any other digital asset or digital commodity that satisfies the scope of ‘virtual currency’ described [in the interpretative guidance].”