23 February 2023 • 8 minute read

US GILTI and Pillar 2: a closer look at the Administrative Guidance

Below, we provide a detailed review of the February 2 Administrative Guidance with respect to the overlay of GILTI within the framework of Pillar 2, which is of particular relevance to US-headquartered multinationals.

Key details

The Administrative Guidance provides more detail on a wide range of technical matters, including how the Pillar 2 GLoBE income and taxes are to be determined starting from financial statements. Particularly for US multinationals, an important component of the guidance is confirmation that the US Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) regime is a controlled foreign corporation regime within the meaning of the GloBE Model Rules, albeit a blended one, and the prescription of a mechanical formula for how US multinationals take into account GILTI taxes in calculating ETRs in the jurisdictions in which they operate, as mandated by Article 4.3.2 of the GloBE Model Rules.

Specifically, the Administrative Guidance confirms that the US GILTI regime, as currently enacted, qualifies as a “Blended CFC Tax Regime” under the GloBE Model Rules, and thus, along with Subpart F, is considered a “CFC Tax Regime” – and the taxes imposed thereunder are “CFC Taxes.”

With US GILTI calculated not on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis, but rather by blending the income and taxes of all group CFCs, a critical unknown prior to the February 2 release was how US multinationals would allocate GILTI taxes to Constituent Entities to determine Jurisdictional ETRs. Many practitioners offered a myriad of potential allocation keys, but also highlighted the complexity of those methods that may be most faithful to the GloBE Model Rules. Instead, practitioners recommended that the adopted approach be as pragmatic as possible.

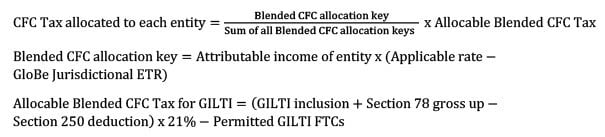

The recent Administrative Guidance uses an ETR-weighted allocation key to allocate CFC Taxes to Constituent and Non-Constituent Entities, as follows:

In addition, the Administrative Guidance clarifies that, for purposes of the allocation key described above, GloBE Jurisdictional ETR will include Qualified Domestic Top-Up Taxes (QDMTTs) only if the CFC Tax Regime jurisdiction (ie, the US) allows a foreign tax credit (FTC) for the QDMTT “on the same terms as any other creditable Covered Tax.”

Elsewhere in the Administrative Guidance, it is noted that QDMTT are computed without regard to CFC Taxes. This is an important clarification and again confirms the OECD’s intent to allocate to the local jurisdiction the primary/first right to tax low-taxed income. Consequently, QDMTTs apply first (assuming creditability in the US), and before GILTI/Subpart F, seemingly precluding any allocation of CFC Taxes given the QDMTT would necessarily raise the Constituent Entities’ GloBE Jurisdictional ETR to 15 percent or greater.

For purposes of the above calculation, below are a few keys highlights:

- The allocation key applies to both Subpart F and GILTI taxes.

- Attributable income of a Constituent Entity is the amount of taxable income included for US tax purposes in the GILTI calculation. Although not specifically addressed, we believe this should include any positive income of a disregarded entity that is otherwise offset by losses of another disregarded entity of a CFC, including a Tested Loss CFC.

- The applicable rate for US GILTI is the statutory rate of GILTI, subject to the Section 250 deduction, and after taking into account the 20-percent haircut. Accordingly, the applicable rate is 13.125 percent (increasing to 16.56 percent for tax years after December 31, 2025).

- If the GloBE Jurisdictional ETR of a CFC equals or exceeds the Applicable Rate, the Blended CFC allocation key for that Constituent Entity is zero, and no allocation of US GILTI tax is made to such entity.

- The allocation key is set to sunset for calendar year taxpayers at the end of 2025, coinciding with the increase in the GILTI rate.

- The allocation key effectively allocates GILTI/Subpart F taxes to the lowest tax jurisdictions, based on magnitude of income, with no CFC Taxes allocated to jurisdictions in which the GloBE Jurisdictional ETR is already set at 15 percent. This may come as a pleasant surprise to US multinationals that feared unusable allocations of CFC Taxes to high-tax jurisdictions that would have further increased the negative Pillar 2 impacts, but it should be noted that this is conditioned on the US providing FTCs for QDMTTs (otherwise, CFC Taxes may be allocated to high-tax jurisdictions).

- Subpart F would also be characterized similarly due to the cross-crediting of FTCs from different jurisdictions. Additionally, as the foreign branch category also blends credits of jurisdictions, although not specifically provided for, we would expect a similar allocation key could be used to allocate the residual US tax on foreign-branch income to any low-taxed foreign branches, using 21 percent as the Applicable Rate.

- It is currently unclear whether QDMTTs would be creditable in the US. Due to the allocation key, the failure for the US Treasury to confirm that a QDMTT is creditable (or Treasury proactively issuing regulations stating that it should not be creditable) will result in the Allocable Blended CFC Tax being allocated to jurisdictions that are already subject to the 15-percent Top-Up Tax, leading to further double taxation. The US creditability will likely depend on how each country specifically enacts the QDMTT in their jurisdictions, as assessed under both the old and new FTC regulations as to the voluntariness of the tax and whether such tax could be viewed as a “soak up” tax. However, the guidance states that, to be considered a QDMTT, the tax must be implemented and administered in a way that is consistent with the outcomes provided for under the GloBE Rules and the Commentary.

- There is a cap on the amount of CFC Taxes that can be allocated to a jurisdiction for “passive income” as defined under the GloBE Rules. Such rule attempts to police the allocation of high taxes to mobile income that could be transferred to a low-tax jurisdiction. Accordingly, the amount of CFC Taxes allocated to a jurisdiction for passive income is capped at 15 percent. Thus, with respect to Subpart F income generated due to passive income, taxpayers should consider such rules in modeling the allocation of US residual tax to local jurisdictions.

- As noted above, given the fact that QDMTTs are utilized prior to CFC Taxes (eg, GILTI) in determining a Constituent Entity’s GloBE Jurisdictional ETR, the US will seemingly cede the primary right to tax low-taxed income to a local jurisdiction. Perhaps Treasury is considering it acceptable to allow source countries the initial right to impose tax to dissuade US multinationals from making tax-motivated decisions to locate activities in low-tax jurisdictions. Query whether low-taxed jurisdictions may forgo QDMTTs or make their application electable (while giving other benefits to its taxpayers) as a mechanism to attract investment in their respective country. However, that then brings into play the application of IIRs and UTPRs in such jurisdictions. CFC Taxes can be applied against IIRs and UTPRs to potentially ameliorate (but not eliminate) their impact.

- GILTI/Subpart F is calculated under US tax principles. Calculation of IRR/UTPRs is based on the accounting standards of the ultimate parent company. The Administrative Guidance provides that calculations of QDMTTs can be done under different accounting standards than the ultimate parent company. Thus, to the extent QDMTTs are enacted, US multinationals that utilize US GAAP may be required to undertake multiple ETR calculations in the same jurisdictions. In addition, ETR calculations under the new US corporate minimum tax (CAMT) may necessitate a fourth dissimilar calculation that requires adjustments from US GAAP, creating compliance and resource challenges for US multinationals.

- It remains unclear whether CFC earnings included in determining a US multinational’s tax liability under CAMT would be considered a CFC Tax and, if so, whether they would be subject to the above allocation key.

- US multinationals should be aware of the impact of non-refundable credits on their US ETR. Non-refundable credits, including the Section 41 R&D Credit, are treated as reducing corporate taxes and depressing ETR. If the US multinational’s ETR is pushed below 15 percent, a subsidiary jurisdiction could theoretically apply a UTPR to capture the delta.

Going forward

The GloBE treatment of non-refundable credits on US multinationals’ ETR was recently highlighted in a strongly worded letter from House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith to OECD Secretary General Mathias Corman, in which Chairman Smith characterized the UTPR as a “fundamentally flawed” measure that will significantly lessen the effectiveness of tax incentives enacted by the US Congress, including the R&D tax credit. Chairman Smith’s letter also warned of “… tax and trade counter measures to protect American jobs, sovereignty and tax revenues.”

While such measures are unlikely to become law in the currently divided US Congress, the recent Ways and Means Committee letter highlights that the US is highly unlikely to enact legislation to conform measures such as GILTI or the recent CAMT to OECD’s GloBE standards. The letter also serves as a reminder to US multinationals to review their US ETR for exposure to non-US jurisdictions’ UTPR taxes.

IN CASE YOU MISSED

Our Global Tax Reform hub houses related articles covering developments in global tax legislation.