27 November 2023 • 18 minute read

Bank on it – Bankable leasing structures for Australian renewable energy projects

Renewable energy is here to stay. Traditional fossil fuel energy generators are being switched off, and the world is moving towards net zero targets with an ever-increasing demand for energy (unmatched by dwindling supplies of non-renewable resources). Developers, investors, lenders and governments alike are directing their attention towards capitalizing on Australia’s untapped potential in the renewable energy market.

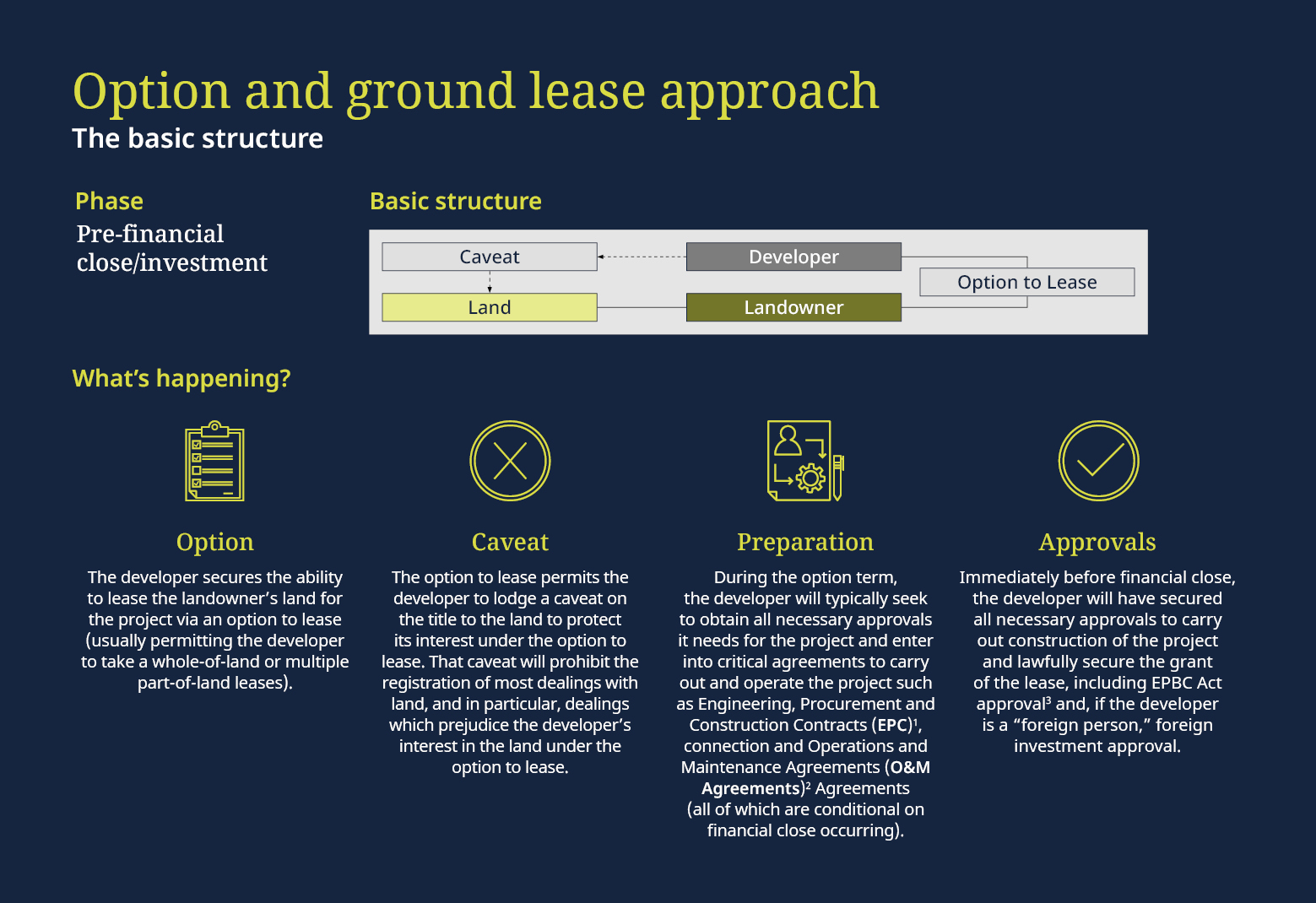

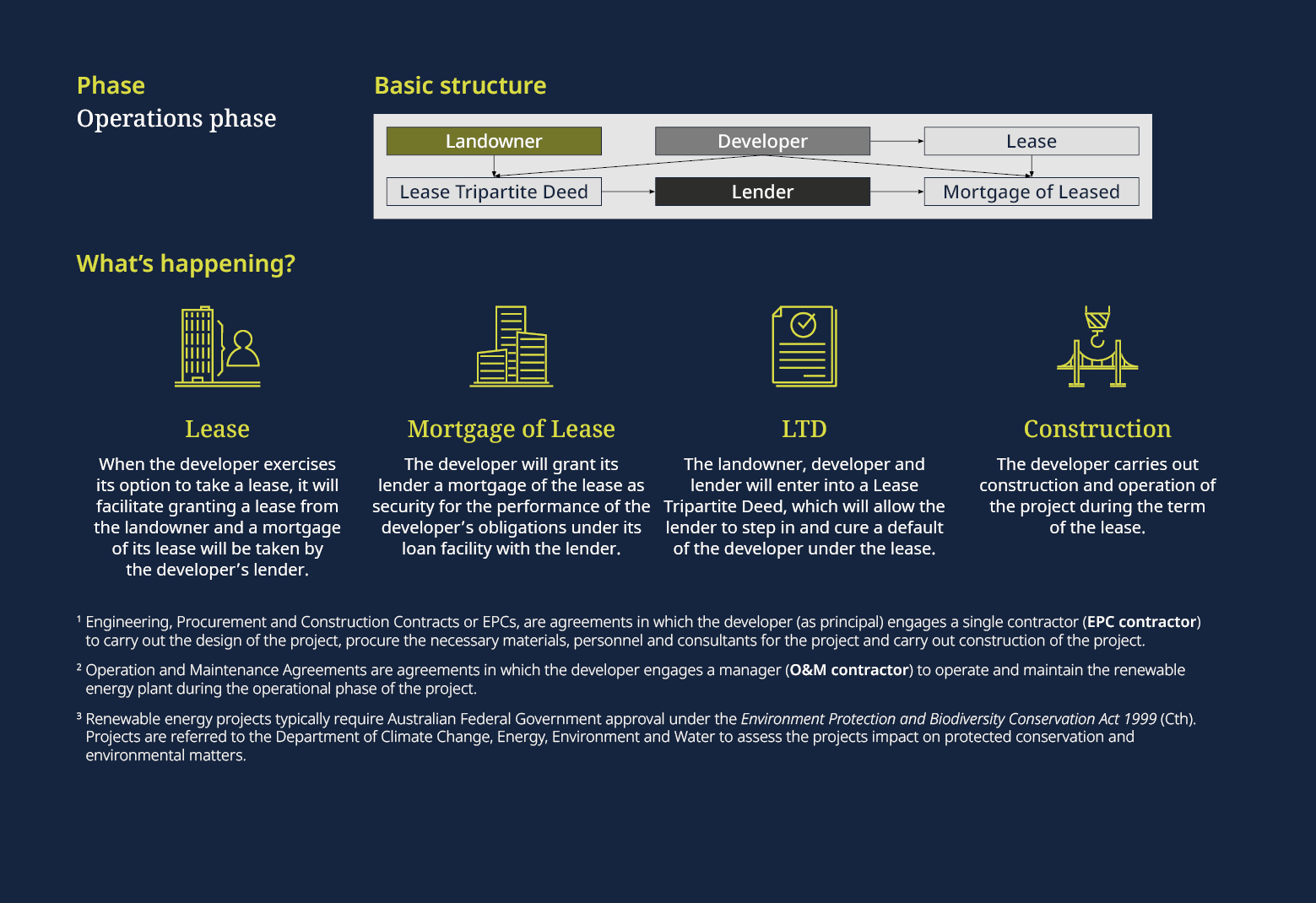

Securing land tenure for a renewable energy project is a critical step in the renewable energy project lifecycle. There are many different land tenure structures that can be adopted to deliver a renewable energy project. This article looks at the benefits and setbacks of four typical leasing structures we see in the market for Australian renewable energy projects.

Pros and Cons

Pros |

Cons |

| Common: This is the most typically used structure for a single lease site for projects such as solar voltaic farms, hydrogen and green hydrogen, pumped hydro and first-to-market single-site projects. | Scalability: At scale, such as for part-of-land wind turbine leases: • the requirement to obtain planning approval to grant the lease can be administratively burdensome and time consuming; and • where a leased site is land locked, access to the site requires dedicated tenure access (usually via a registered easement) to a public road. |

| Bankable: The simple bankable structure makes it favorable to investors and lenders. | Capital investment: Rent is typically at the high end, particularly during the construction phase where the renewable energy plant is not selling electricity to the grid, requiring a higher capital investment. |

| Stages: Where the option to lease permits multiple exercises of the option, the project can be developed in stages and the caveat maintained to protect the developer’s interest in the land and project (in which case the lender usually requires a Caveat Tripartite Deed to allow the lender to remove the caveat if the developer defaults under its loan facility and the lender takes enforcement action). |

Term: Because construction of the project is carried out after the lease commences, the economic life of the renewable energy plant exceeds the initial term of the lease. This can be solved by the lease triggering an extension of the term on commissioning of the project so the extended term aligns with the economic life of the renewable energy plant. Certainty: Requires a large degree of certainty of the size and location of the renewable energy plant on or before financial close so is less attractive for micrositing and large-scale part of land projects (eg wind farms). Access: Landlocking may be an issue if not appropriately addressed in the option documents since the lease is over only part of the land. |

Construction and operational lease approach

The basic structure

The basic structure of a construction and operational lease is the same as the option to lease and ground lease approach except that:

- the developer exercises its option to take a whole- or part-of-land construction lease;

- the developer constructs the renewable energy plant under the construction lease; and

- when practical completion and commissioning of the renewable energy plant is complete, the developer surrenders the construction lease and the landowner simultaneously grants the developer an operational lease to operate the renewable plant over the project lifecycle.

Pros |

Cons |

| Lease footprint: The operational lease will accurately reflect the “as constructed” footprint of the renewable energy plant. As a result, the lease footprint can be as small as possible, which is particularly useful for micrositing and wind turbine installations. | Landowners: The developer obtaining a whole-of-land construction lease may be challenging as landowners can be reluctant to grant a whole-of-land lease to a developer because the lease grants the developer exclusive possession of the land, allowing the developer to exclude the landowner from that land. This is the case even where: parts of the land not used for the project are licensed back to the landowner (given a license is not a secure form of tenure). |

| Term: The term of the operational lease can align easily with the economic life of the renewable energy plant since the developer exercises the option to take an operational lease only after practical completion and commissioning of the renewable energy plant has occurred. | Registration: Two lease registration steps are required. |

|

Planning approval: Where the developer exercises its option to take a whole-of-land construction lease, planning consent is not required to grant the construction lease. Planning consent to grant an operational lease is deferred until after financial close and is obtained during the construction phase of the project. Rent: Typically, the rent during the construction phase is much less under the construction lease than what is payable under the operational lease, requiring less up-front capital investment. Nomination: The option to lease typically allows the developer to nominate a third party to be the tenant under the construction lease and/or operational lease, giving flexibility to appoint the constructor and operator of the renewable energy plant. Security: The lender can take registered security over the construction lease and subsequently on the operational lease, making this structure favorable for debt financed projects. |

Document heavy: The structure can be a little document heavy, as two leases are required. Lenders may also have requirements for more than one suite of security documents and tripartite deed arrangements with the landowner. |

Whole-of-land lease

Slightly less common than the structures referred to above, is the situation where the developer exercises its option to take a lease over the whole of the landowner’s land. The basic structure is the same as the option and ground lease, except that:

- Option: the developer exercises its option to take a lease over the whole of the land and not part of it.

- License back: the lease obliges the developer to grant a license back to the landowner for those portions of the land which aren’t required for the project.

- Planning approval: local council planning approval to grant the lease is not required.

Pros |

Cons |

| Bankable: The simple bankable structure makes it favorable to investors and lenders. | Landowners: Landowners can be reluctant to grant a whole-of-land lease to a developer because the lease grants the developer exclusive possession of the land, allowing the developer to exclude the landowner from that land. This is the case even where parts of the land not used for the project are licensed back to the landowner (given a license is not a secure form of tenure). |

| Flexibility: Allows relative flexibility to build a renewable energy plant on the land as a whole, but this is sometimes limited to a defined construction zone within the land boundaries. | Term: Because construction of the project is carried out after the lease commences, the economic life of the renewable energy plant can often exceed the initial term of the lease. This can be solved by the lease triggering an extension of the term on commissioning of the project so the extended term equals the economic life of the renewable energy plant. |

|

Access: Landlocking is not typically an issue since the developer can usually access a public road connected to the lease boundary. Cable daisy-chaining: Cabling and connections between the renewable energy plant is less problematic as the cables and connections can be installed and operate under the terms of the lease. Nomination: The option to lease typically allows the developer to nominate a third party to be the tenant under the lease or to stand in for the developer under the option to lease permitting investment before, at and after financial close. Security: The lender can take registered security over the whole-of-land lease at financial close, making this structure favorable for debt-financed projects. |

Rent: The whole-of-land lease approach is only financially viable where rent is tied to something other than the area of land leased (eg tied to the nameplated MV hours per annum of the renewable energy plant). |

Caveat-backed construction license approach

Even less common than the other structures, but still very useful, is the caveat-backed construction license approach:

- Construction: Option to lease grants the developer a license to build the renewable energy plant on the land during the term of the option to lease.

- Operations: Operations lease is triggered on practical completion and commissioning of the renewable energy plant.

- Security: The developer secures its interest in the project before the operations lease is granted by lodging a caveat on the title to the land.

Pros |

Cons |

| Lease footprint: The project lease and the locations of other renewable energy plants will accurately reflect the as-constructed footprint of the renewable energy plant. As a result, the lease footprint and associated tenure can be as small as possible, which is particularly useful for micrositing and wind turbine installations. | Security: Using this structure hinges on whether the project lender agrees to advance under the loan facility without any registered security (since the developer does not have a lease during construction for the lender to take a mortgage over). Instead, the lender needs to rely on an equitable mortgage, its rights under the Caveat Tripartite Deed and any general security the lender takes over the developer’s assets. |

| Term: The term of the lease can align easily with the economic life of the renewable energy plant since the developer exercises the option to take a lease only after practical completion and commissioning of the renewable energy plant. | Document heavy: This structure is more document heavy then the other structures because the lender will typically require tripartite deeds from the EPC contractor and O&M contractor, allowing the lender to step in and cure a default of the developer under the EPC and O&M contracts. |

| Planning approval: Planning consent to grant a lease is deferred until after financial close and is obtained during the construction phase of the project. Typically a lender will require some form of in-principal approval from the local council of the general location of the renewable energy plant. Registration: Unlike the construction and operational lease approach, only one registration step to obtain an operations lease is required. |

Where to from here?

The land tenure structure used for a renewable energy project is an important consideration for the renewable energy project lifecycle. Ultimately, the land tenure structure used requires balancing the needs of the developer and the project against those of the project’s investors, lenders, landowners, and other key stakeholders.